Of all the social and economic discussions that have arisen since the advent of the globe-spanning pandemic, the conversation around housing inequality is an important one. As many news outlets have reported, COVID-19 has taken a bigger toll – physically, mentally and economically – on Black and other racialized communities. And this impact includes Canada’s precarious housing situation.

By definition, housing inequality is a form economic disparity and can be directly linked to systemic racism and social imbalance. But it has other far-reaching consequences that COVID-19 has amplified.

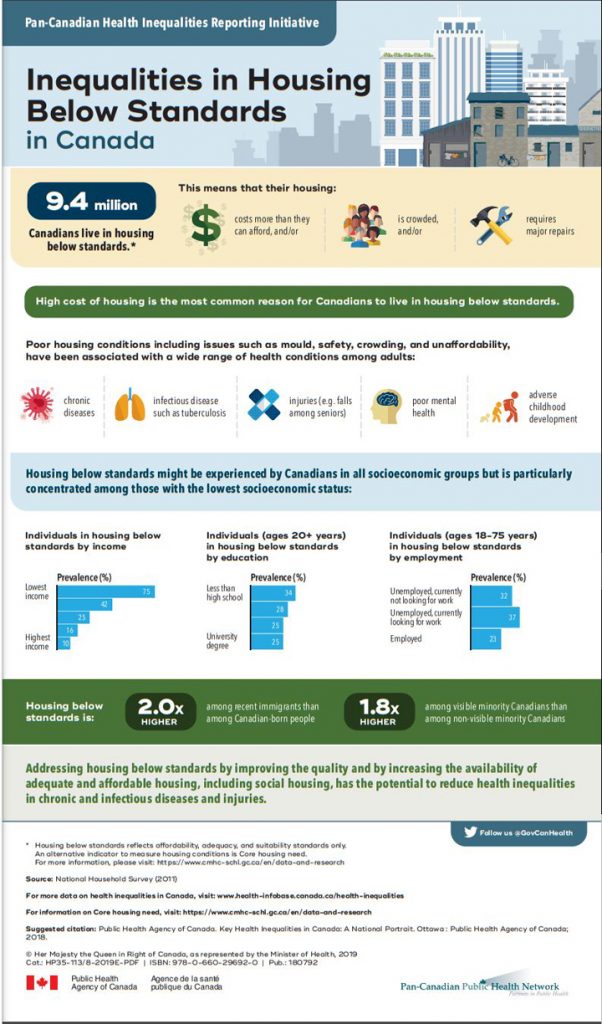

According to a Government of Canada report, 9.4 million Canadians live in housing that is well below national standards, meaning that the places they call home costs more than they can afford, is overcrowded and often requires significant repairs. This data was compiled prior to COVID-19 – the devastating pandemic that has resulted in major repercussions across various sectors, not least of which are the lack of affordable and well-maintained housing and rental spaces.

For Dr. June Francis, director of the Institute for Diaspora Research and Engagement at Simon Fraser University, much of this recent dialogue surrounding COVID-19 and housing inequality in Canada comes down to the assumptions that were made early on by public health officials.

“For example, in Toronto 81 per cent of COVID-19 cases were in postal codes that were in disproportionately racialized communities,” she says. “When we look at the assumptions that were being made when public health officials first decided on what measures we would take, what assumptions did they make about the housing situation of people? First of all, they told us to ‘shelter in place’, right? Now, if you need to shelter in place, you need a place to shelter in.”

Related: 10 Facts About Racial Injustice in Canada That Will Shock You

In addition to her work with the BC-based university, Francis is co-chair of the Hogan’s Alley Society (HAS), a non-profit organization comprised of activists, professionals and community leaders that advocates for Black Vancouver residents – and other marginalized communities – to be more involved in city planning and community development. For Francis, COVID-19 has only exacerbated already increasingly untenable living arrangements for a large portion of Canada’s population.

“Many people live in crowded, intergenerational circumstances where at least one or more members of their family didn’t have jobs that offered them the comfort of sitting at their computer at home while social distancing,” Francis says. “These are people who work in supermarkets, on transit, those who deliver our goods and those working in health care. Despite all this, they have had to go out and face COVID and then come back home to their families [every night].”

As a result, transmission rates skyrocketed in certain pockets of major cities, hitting older vulnerable senior citizens the hardest, she adds.

“But what I found most upsetting was that public health [officials] disregarded these circumstances when they came up with their public health support,” she says. “There were no plans for these people.”

Jino Distasio, a professor from the University of Winnipeg whose work focuses on marginalized communities and neighbourhoods in Canadian cities, echoes the sentiment, pointing to the economic and housing disparities between different regions across the country. “[COVID-19] really magnified the challenges faced by Canadians that are low-income and live in marginal housing,” he says. “[Additionally], people occupying low-quality housing don’t always have access to the same outdoor amenities in a pandemic – access to open space or walkable communities. They’ve been shut in for months, in crowded homes.”

Related: What is Food Insecurity? FoodShare’s Paul Taylor Explains (Plus What Canadians Can Do About It)

This came as no surprise to Francis, however, as she points directly to Canada’s history of systemic racism. “Housing inequality is related to the fact that [throughout] history, Canada’s relationship to Black people has been that we don’t belong here,” says Francis, who was born in Jamaica. “We’re not considered ‘true Canadians’ and if we were ‘true Canadians’ it would be in servitude to others. The problem with city planning, even to this day, is the tendency to see a city as white and relatively well-off. [It] primarily concerns itself with planning for its white citizens and people of property and people of ‘value.'”

The Government of Canada study lends further credence to the point, citing that substandard housing is two times higher among recent immigrants to Canada versus those born here. Housing inequality is also 1.8 times higher among visible minorities.

Francis references the institutional and private exclusions Black and other marginalized communities have faced when it comes to affordable housing. “When you don’t get access to home ownership, people are set behind for the next generation,” Francis adds. “When Black Canadians are asked why they’re poor or housing insecure, almost everyone points to private discrimination. They show up [to view a property] and suddenly the house is no longer available. Or now it’s going to cost them more because there’s a penalty for being Black. The smallest infraction is a reason to be kicked out – and you’d better not be a Black woman with children or you’ll never get a house. If you don’t have proper housing then all the other things fall apart. It affects education, health, economic opportunities and causes social isolation and exclusion. Housing is foundational.”

Related: How Food Injustice Inspired This 23-Year-Old to Start Her Own Farm, Plus Her Advice for You

In the past year, with protests arising across the globe, Canadians witnessed first-hand the systemic racism that permeates every facet of daily life – so much so that housing inequality in and of itself can have a devastating impact on health. Although it’s a less commonly discussed side effect of housing insecurity, the fallout is inevitable.

“Access to quality housing can have a huge impact on health due to inadequate ventilation or heat – it’s also not just overcrowding, it’s influenced by families having enough money to pay for shelter and that can cast a heavy burden on people’s ability and their mental health,” Distastio points out. “We know that access to quality neighbourhoods and amenities, like green spaces and light and fresh air, can impact well-being.”

Housing inequality is not just unique to expensive cities like Vancouver or Toronto, Distasio adds, and we need look no further than the treatment of Canada’s Indigenous populations.

“Having worked a lot in prairie cities, we do see that Indigenous Canadians are increasingly shut out of the market,” he says. “They’ve disproportionately experienced homelessness. Their experiences in the housing market are really problematic. Although we’ve seen some gains there’s still significant challenges. Historically, we’ve looked at the federal government to be a provider of resources for provinces to build and maintain affordable housing, and we know that in the early 1990s federal support for affordable housing really fell off. That shifted the burden to provinces and municipalities that fell further and further behind. So in and around 1999, when Toronto was the epicentre of a national housing crisis, we slowly pulled the federal-provincial-municipal government back to the table to think about how we could build and maintain more affordable housing. Although we haven’t succeeded to any great extent, the national housing strategy at least signaled a bit of a return of the federal government in the affordable housing file.”

Related: Ren Navarro on Diversity in the Beer Industry – and How Companies Can Improve

Distasio believes that, at the end of the day, the vast majority of Canadians want to see all Canadians succeed, adding that what we’ve experienced during COVID has magnified the cracks in the system.

“We’ve exposed the fact that not all Canadians have access to technology to learn at home, not all Canadians have the ability to remain at home and feel safe without feeling crowded or concerned about whether or not they can pay the heating bill,” he says. “The pandemic has really put the Canadian social policy under the microscope.”

So, what can Canadians do about it?

“I think we have to get back to the basics where we see investments in social and community planning and affordable housing as the social safety net that makes Canada the great country that it is,” Distasio says. “I think we’ve forgotten that path.”

Looking for ways you can help? Consider donating to the following charities and organizations: Aboriginal Housing Initiative, Calgary Homeless Foundation, Canadian Housing and Renewal Association, Centre for Equality Rights in Accommodation, Fred Victor Centre, Habitat for Humanity Canada, Hogan’s Alley Society, Oxfam Canada and Youth Without Shelter, among others.

You can also sign a petition that helps fight for housing equality and communicate with your local elected officials for the need for change.

Related: On a Budget? Here are 11 Ways You Can Still Support Social Justice Issues in Canada

Feature photo and Dr. June Francis photo courtesy of Getty Images; infographic courtesy of the Government of Canada; Jino Distasio photo courtesy of University of Winnipeg.

HGTV your inbox.

By clicking "SIGN UP” you agree to receive emails from HGTV and accept Corus' Terms of Use and Corus' Privacy Policy.